He Should Stay Here; We’ll Be His Parents.

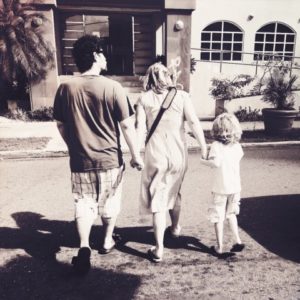

Anthony and his wife Mariana met in graduate school while pursuing their Masters of Fine Arts. After graduating, they moved to Oakland, California and lived the lifestyle of young artists, enjoying their childfree existence. As their relationship deepened, they agreed that they would not become parents. For Mariana, the choice seemed predestined, as she’d been told she was unlikely to be able to get pregnant. For Anthony, his own childhood — characterized by extensive contact with the criminal legal system, living in foster care, disconnect from biological family, and being uprooted — informed his reluctance to become a parent.

Anthony grew up in the projects of East and South Boston with a cohort of older and younger half siblings, navigating blended family and community racism as a white and Mexican person who appears racially ambiguous. In Anthony’s own words, his childhood was “super complicated, but in ways that weren’t apparently complicated until I was older. I think the nature of both childhood, and everyone’s individual family experiences, is that what you’ve got in front of you, particularly when you’re young, just is what it is. It’s the norm because it’s what you know. The way that I grew up was in Boston with my mother and siblings as my main family unit.”

Eventually, his older siblings left to make their own ways in the world after difficulties with their mother. At 14, Anthony was removed from his mother’s household at her request. After a heated argument, preceded by months of deteriorating relations (including escalating alcohol and drug use by Anthony), his mother called the police saying she feared for her safety. Anthony was arrested and spent the weekend in jail. “When I hit my adolescence, I too had difficulties at home with my mother, and I ended up in foster care,” Anthony says. At this point in his life, he fell out of touch with his biological mother and siblings. After bouncing around for several months in group homes, he found new family with his foster mother, Cindy; her adopted daughter, Michelle; and her biological son, Matt. Cindy, Anthony says, provided “the kind of implicit safety that comes from stability and predictability.”

Anthony’s time in foster care allowed him to finish high school and build a village of support that would last into adulthood. Central to this village are friends with whom he created graffiti. He speaks to the power of this community, saying, “Graffiti saved my life. That’s genuine. Me and some of my friends that are still some of my closest friends in the world were too busy painting. That got us in trouble, including legal trouble, but that kept us out of the drug game, and that kept us out of gunfights, literally. Our lives are significantly better off than they would have been without graffiti. A sense of home, a sense of belonging, and a sense of purpose emerged out of all those things.”

After moving out of Cindy’s home at 18, Anthony worked to stay in touch with Cindy, Matt, and Michelle. Michelle struggled with mental illness, substance use, and a number of health issues that accompany both. Anthony did what he could to help her once he returned to Boston. “I helped her move a couple of times from shelter to shelter, was trying to advocate alongside her with her different social workers. There’s a limited amount that you can do, particularly if somebody doesn’t want the help, particularly if they’re in bad shape like she was.” Michelle had two children, one of whom Cindy cared for. Michelle was raising her second child Anto when, Anthony explains, “she had a dissociative episode, and social workers came, got involved, saw where she was, and did an emergency removal of her kid. I was top of the list of people they called.”

What Anthony and Mariana assumed would be a weekend stay became permanent. Although Cindy was willing to care for Anto, she no longer lived in Massachusetts, so she could not take custody of him until legal arrangements were made. Anthony and Mariana agreed to foster Anto in the interim. In the ensuing year, the courts decided Michelle would not regain custody of her son. The need for temporary custody shifted to finding a permanent adoptive home for Anto. By that time, little Anto was so settled in with Anthony and Mariana that they made the decision to keep him with them. “Ethically, it just wouldn’t have been the right thing to do to remove him from us, because the process had taken so long, and we had bonded,” Anthony explains. “Removals are traumas…we just said, ‘He should stay here; we’ll be his parents.’” Despite their earlier decision to not have children of their own, when called upon by people Anthony had come to know as family, the couple stepped into the struggle, love, and growth that raising children requires.

Anthony and Mariana had the help of Mariana’s family, as well as that of friends they leaned on for support and community. “I’ve got great friends and good connections,” Anthony says. “We built what we needed there to get by and do well. In Boston, my friends have kids his age. They can go hang out. We can all get together in somebody’s backyard, let the kids run around, have some beer, shoot the shit, do sleepovers. I had a community of people that were also in foster care when they were kids, but also are a community of people that are raising adopted kids, multi-ethnic families, folks that just get it implicitly.” For Anthony, all of these people are family. He says that family is “the people that I choose to be bound to, and committed to, and loyal to. Most of that is not blood, which is totally fine by me.”

Anthony and Mariana had the help of Mariana’s family, as well as that of friends they leaned on for support and community. “I’ve got great friends and good connections,” Anthony says. “We built what we needed there to get by and do well. In Boston, my friends have kids his age. They can go hang out. We can all get together in somebody’s backyard, let the kids run around, have some beer, shoot the shit, do sleepovers. I had a community of people that were also in foster care when they were kids, but also are a community of people that are raising adopted kids, multi-ethnic families, folks that just get it implicitly.” For Anthony, all of these people are family. He says that family is “the people that I choose to be bound to, and committed to, and loyal to. Most of that is not blood, which is totally fine by me.”

When Anthony, Mariana, and Anto moved away from Boston for career reasons, they found it harder, and Anthony misses the “buttressing,” as he describes it, “that comes along with deep roots and people that you have these affinities with, that tacitly understand what you’re dealing with and who you are.”

But his childhood gives him some perspective on how much harder things could be. “People like me, in terms of just the descriptive statistics about who I was demographically, are supposed to fail. The only reason that I wound up where I am, is because of a really unlikely mix of luck and circumstance, and some stubbornness on my part. I wouldn’t call it hard work,” Anthony says.

Anthony, a former social worker who works on economic justice issues, is also clear on the role policy approaches can play in making life easier for people who experience marginalization. “Having fewer strings attached to more generous social programs, including cash, not just in-kind transfers like SNAP or WIC, would be where I would start. Then it would be about having really good public infrastructure, including good public schools and libraries, public transit, public hospitals, housing that’s public and affordable — or free — and safe and desirable. That is the policy platform, I think, that I would embrace and promulgate if I could.”

Anthony also acknowledges that changing personal and systemic biases are important. “We also need to think about how to, in a very structural and meaningful way, deal with a lot of the biases that are baked into our culture, primary among them racism and sexism, but also homophobia and classism, among many other things. It’s impossible to disentangle the structural policy responses of just giving people the things that they deserve, and need to flourish, from these other pieces that are built into us, and associated with stigma and bias and prejudice. They’re difficult to talk about in isolation. They’re very intertwined. It’s critical that we try to respond to both of them simultaneously and not think one will fix the other.”

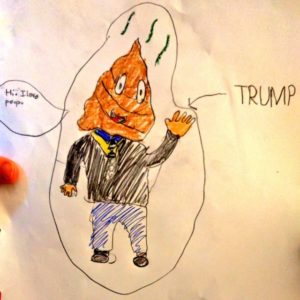

Looking back on a challenging journey, Anthony offers some perspective on his path to parenthood: “This wasn’t what I imagined for myself, and wasn’t what I planned, but I can say that it’s made me a better person. If you ask my wife or friends about what fatherhood has done for me, they’ll probably tell you I’m kinder, more patient, mellower.” He also describes the joy any parent would recognize in seeing their own best aspects mirrored in their children. “Anto is totally our kid,” he says, “Mariana and I met in grad school because we were two of the only people making political art in the run-up to the Iraq War, and now Anto is a budding political cartoonist…you should see his anti-Trump drawings,” he says with a laugh.

Looking back on a challenging journey, Anthony offers some perspective on his path to parenthood: “This wasn’t what I imagined for myself, and wasn’t what I planned, but I can say that it’s made me a better person. If you ask my wife or friends about what fatherhood has done for me, they’ll probably tell you I’m kinder, more patient, mellower.” He also describes the joy any parent would recognize in seeing their own best aspects mirrored in their children. “Anto is totally our kid,” he says, “Mariana and I met in grad school because we were two of the only people making political art in the run-up to the Iraq War, and now Anto is a budding political cartoonist…you should see his anti-Trump drawings,” he says with a laugh.

This piece was originally published in September 2017 as part of Family Story’s All Our Families story-telling project.