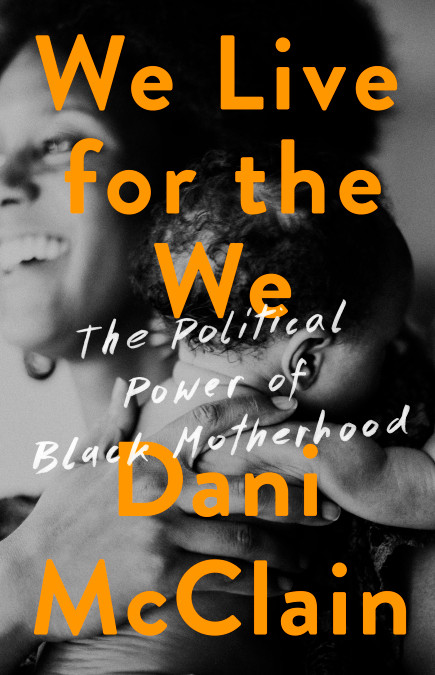

Q&A With Dani McClain, Author of ‘We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood’

Earlier this month, Dani McClain’s new book, 'We Live For The We,' was published by Bold Type Books. In it, the author, who regularly writes and reports on race, reproductive health policy and politics, discusses the political power of Black motherhood and how to raise Black children in such turbulent times. We talked to her about what she learned writing the book, what she’s doing to raise a joyful Black child, and the importance of community, no matter where you live.

Family Story: Congrats on your new book. Let’s start with the big question first: What is the political power of Black motherhood?

Dani McClain: There’s a certain power in having to navigate a society that’s not set up for your family. I think that Black mothers and families have a legacy of knowing how to establish communities and home cultures that are comforting and affirm our children even when the world around us doesn’t. We have a history of figuring out how to support our children, who many may think are inferior based on the color of their skin, and shepherding them into adulthood, and there’s great political power in that.

How are the mothers of Black children you spoke with for your book able to set their very realistic fears aside and raise their kids with dignity and joy?

I was pregnant with my daughter during the summer of 2016. This was around the same time that Alton Sterling was killed in Baton Rouge and Philando Castile was killed in Minnesota. I was really clued into the political climate of the country, and I got scared in a way I never had before. I wasn’t able to look at it with the detachment I had as a journalist. I felt it on a very emotional level. That was my introduction into being a Black parent.

Parenting, in general, causes fear and anxiety. But being a parent of a Black person in this country is cause for a lot of fear. So I asked many people: How do you deal with this fear? What so many told me was to play. You just play and encourage your kid to be a kid. Let them experience joy and develop a sense of wonder about the world. This country doesn’t let Black kids be kids, so it’s our job to give them their childhood. We can’t become so consumed by our fears that we become overly protective and try to shelter our kids and smother them. That was really helpful to hear.

My own daughter is still really young, so we’re still very focused on the play aspect. We’re always dancing and singing. I do everything I can to give her opportunities to laugh. I just want her to learn that we deserve joy and to feel carefree and to feel free in our bodies.

In your research speaking with so many other Black mothers, did anything surprise you?

I was born and raised in the Midwest, and currently live in Cincinnati. We have a ton of family support here, and it’s lovely that my daughter gets to be with her grandparents and other family members so much. But I used to live in New York and Oakland, so I sometimes romanticize life on the coasts, which I assumed would provide better access to schools, playgrounds, nanny shares and other options that you can only find in a politically progressive place.

But I interviewed a mom in the Bay Area who’s struggling to find a racially inclusive school for her daughter. You’d think that would be easy because she lives in such a progressive place, but it doesn’t matter. I also spoke with a mom in Georgia, who has a wonderfully supportive setup for her two sons. She’s been able to piece together a community for them through her contacts in community gardening and other local programs and lots of friends. It helped me realize that it’s not about geography as much as it is about being proactive in putting together the right kind of community for your family.

You say that “the wider world too often tells us we are: criminal, disposable, lazy, undeserving of health or peace or laughter.” What should white folks who want to be allies be teaching their children to change this?

All I can say is to break your participation in White supremacist thinking and behavior. But really, I’m not interested in telling White folks how to do that. That’s why I liked writing this book — I got to really center Black people. I gave them a platform, which was such an honor and a privilege. We’re so used to speaking up in response to something White folks did or said. But with this book, I’m just not interested in that.

What are you hoping folks take away from your book?

My true focus is this: Given that this country is such a challenging place to raise Black kids, what can we do to make it a bit easier on ourselves? We have to turn to each other and build relationships based on trust, even if it’s in tiny, micro ways, we have to work together in our communities. And remember that not everything has to be to scale. We don’t always have to tackle the biggest problem or have the most resources. Sometimes it just helps knowing we’re there for each other.