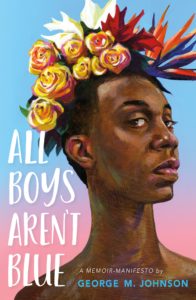

Q&A With George M. Johnson, Author Of ‘All Boys Aren’t Blue’

I assumed everyone knew I was gay, but no one had the language to talk about it. So we just didn’t, and I kept on hiding it. I’m not blaming my family, they just didn’t have the tools.

In a series of deeply personal essays, journalist and LGBTQ activist, George M. Johnson tells his story of growing up as a Black queer boy in New Jersey. In his young adult memoir-manifesto — to be released in April — he shares his experiences not only with racism and homophobia, but also family, friendship and Black love. We recently sat down with Johnson to talk about his debut book as well as “code-switching,” losing his virginity, going to the dentist and writing a different kind of Black memoir.

For those who haven’t been paying attention, what are some of the issues facing Black LGBTQ youth in the United States today?

There are so many issues, but primarily, we don’t know how to handle kids who start exhibiting queerness at an early age, at home or at school. There is no infrastructure set up or road map on how to handle that. So we still see a lot of policies that negatively affect queer kids. Then, when you add the intersection of race, there are additional layers of discrimination.

We’re starting to see an uptick in queer black boys who are dying by suicide, and as a society, we’re not talking about it enough. These kids feel like they don’t fit in because of their race, but they also have this queerness that their community doesn’t understand, so they also feel like they have no community.

We can’t forget the story of Nigel Shelby, the gay teenager who took his own life last year after being bullied. His family supported and loved him, but his family couldn’t be with him at school every day, where he was being attacked. We need to address this on a macro level. Yes, we need to look at how we treat these kids at home, but also at school where they spend so much of their time.

To that point, your family surrounded you in love and support. Why wasn’t that enough to protect you from discrimination?

I knew I had love and support, but there was still a barrier when it came to talking about my sexuality. I knew they loved me, but I wanted the space to talk about it at home. I wanted to tell my mom I liked boys! I assumed everyone knew I was gay, but no one had the language to talk about it. So we just didn’t, and I kept on hiding it. I’m not blaming my family, they just didn’t have the tools. I just wish one of them, at any point, would’ve asked me.

The story of you being brutally bullied at the age of 5 is difficult to read. How did that event – during which your attackers kicked out many of your teeth – affect the rest of your life?

Because my baby teeth were kicked out, my adult teeth came in too early and I was ashamed of how I looked. So I very rarely smiled. When I look at old pictures, I’m shocked to see one of me smiling. Even now in pictures, I don’t post the ones of me smiling. On top of that, I went to the dentist this week for the first time in 11 years. I’ve just been too scared and ashamed. I wish people understood how long trauma can affect a person – I’m 34 now and just getting the confidence to do something about my teeth.

According to the Human Rights Campaign, 42% of LGBT youth say the community in which they live is not accepting of LGBT people. To get by in your community, you talk about having to “code-switch,” or change your language depending on your audience, at an early age. What other ways did you cope?

I always had to watch what I said around different groups of people. One time, I let the word “honey” slip in front of a group of guys, and I’ll never forget the fear I felt in that moment. That was gay language! I got really good at deleting my Internet history so I could Google all the gay things I wanted without anyone finding out. I’d also drive to other towns to go out to gay clubs so I wouldn’t know anyone.

Before I came out, the only time I could really be myself was when I was alone.

Eventually, you made your way out of the closet. Can you think of a time when you felt most seen?

It wasn’t until I lost my virginity, which I talk about in the book. That was the first time I was in control of a situation that involved my sexuality. I was in control, no one was mocking me or calling me a “faggot,” and it was a positive experience. I just still wonder if he knew that I was a virgin.

Other than wanting to put Black queer kid literature out there, why else did you write this book?

I wanted to tell a different kind of Black story. A story of a Black family that may not have always gotten it right, but they did the best they could with the knowledge that they had. My story is not steeped in trauma and tragedy, and yes, I’m Black and gay, but my family never disowned me. They are my safe space. If anything, this book is a love letter to my family and what their support has always meant to me.